Vibecoding AI Agents

A detailed walkthrough of my journey to get two ai agents to collaborate in a simple grid world

Introduction

The goal is to get two ai agents to collaborate in a simple grid world. The setup is simple, a small grid world with one player and two agents. The player moves on the grid and the agents try to capture the player. There's no hard‑coded playbook.

Can they discover trapping and flanking behaviors on their own if I give them the right training signals and constraints?

This post is a narrative of that journey. I explain what each idea tried to achieve, what actually happened on the board, and why some approaches nudged the agents toward teamwork while others quietly broke it. The goal isn't to prove a theorem; it's to share what it felt like to chase collaboration in code.

Why I started this

I've always loved the idea that two simple agents could learn to work together without me scripting their moves. Put them on a grid, add a player, and let them figure out how to trap. It felt approachable, like something I could build and iterate on in evenings. This is a story about that project. I'll go phase by phase: what I tried, what actually happened (good and bad), and what I learned.

A quick shoutout to this 2-minute-paper video that I sparked interest for reinforcment learning in me back in 2019.

Phase 1 — Two independent DQNs (and the first surprise)

I began with the simplest thing I could think of: two separate DQNs, one per agent, both trying to catch a moving player. No shared parameters, no message passing, no team objective. Each agent just maximized its own Q‑values.

Watching the first few thousand episodes was eye‑opening. The agents moved. They learned. And yet they didn’t behave like a team at all. They converged to something that looked like racing: both agents sprinted toward the most obvious path to the player, frequently falling into a line behind each other. If one “stole” the capture from the other, neither seemed to care. The training curves looked fine; the behavior didn’t.

I wrote in my notes that night: “Independent RL treats teammates like moving obstacles.” That became the theme of this phase. Nothing in the setup nudged them to form roles or to split angles. They simply were two single‑agent learners in the same world.

What I learned:

- Coordination doesn’t magically fall out of independent Q‑learning.

- If two agents share a goal but not a training signal, they will collide in intent.

Phase 2 — Shared reward (hello, lazy agent)

The next change was very “coach brain.” I thought: let’s reward the team, not the individual. So if either agent caught the player, both received the same positive reward. Surely that would encourage teamwork, right?

It did the opposite. I ran several seeds and saw the same shape: one agent got increasingly passive. When your teammate can do the work and you still get paid, the optimal move often becomes “do nothing.”

This was my first real encounter with the lazy agent problem. It was super funny to watch lol.

What I learned:

- Equal split rewards can unintentionally promote inaction.

- If effort isn’t required, effort won’t show up.

Phase 3 — Sharing a single brain cell + better rewards

At this point I wanted a minimal way to let the agents align without changing the whole training pipeline. I added a small consensus module: a network that looked at global information and produced a shared embedding. Each agent’s DQN took this embedding alongside its local state.

Think of this like a common brain cell that both agents share.

On top of that I updated the rewards to be more aligned with the team's goal. Instead of only rewarding capture, I started measuring the player’s escape routes—how many neighboring cells the player could move to next step. If that number went down compared to the previous step, the team got a positive reward. If it went up, a small penalty. Captures still paid a lot, but most of the day‑to‑day learning came from shrinking space.

Two things happened almost immediately:

- The agents began to “cut off” the player instead of tailgating it.

- The consensus embedding started to matter a lot, because there was now a team‑level signal that required coordinated positioning.

I don’t want to oversell it. But for the first time I saw organic positioning emerge: one agent approached from one side while the other curved to reduce options. When the player had only a couple of valid moves, captures happened naturally.

What I learned:

- Shaping the world (escape routes) teaches the game’s geometry, not just its scoreboard.

- Team signals make shared context actually useful.

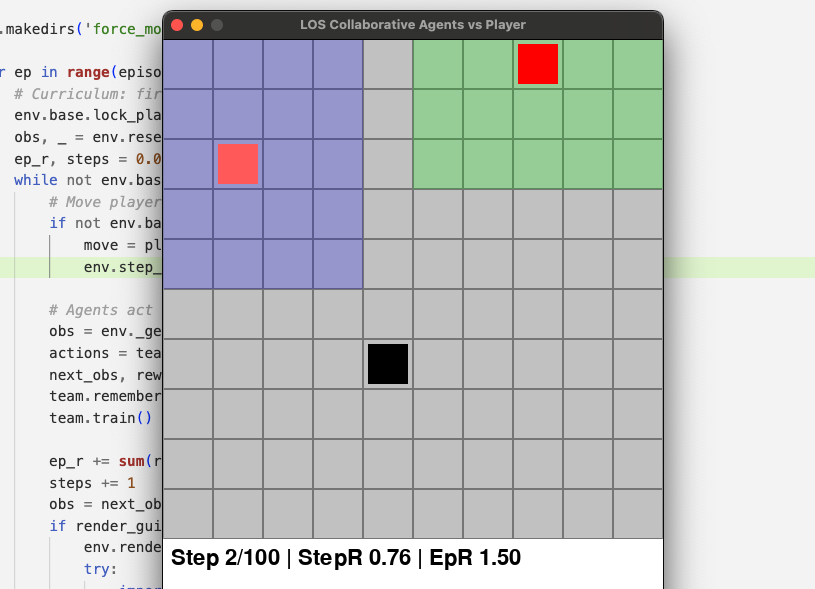

Phase 4 — Line of Sight (and why it humbled me)

After the escape‑route win, I wanted to test real collaboration under uncertainty. I turned on partial observability. The first attempt was a tight 8‑neighbor LOS (Chebyshev radius 1). Later, I doubled it to a 5×5 radius (still small).

Agents only saw the grid within this radius; the player’s position was None when outside LOS.

To help the agents, I tried all of the following:

- Encoded “player not visible” explicitly as (−1, −1) in state.

- Raised exploration when blind (epsilon floor) so they wouldn’t freeze.

- Added a reverse‑move penalty to dampen flip‑flopping.

- Added a stuck penalty for not moving.

- Built a visible overlay so I could literally see what each agent could see.

- Added a curriculum: for the first ~300 episodes, the player stayed put in a corner; later it moved normally again.

And then I trained. And waited. And watched.

The agents did not learn much. Sometimes one agent would chase decently if I (as the player) drove straight into their LOS cone. The other agent often wandered. A lot of wins were accidental situations where the player walked into them, not traps built intentionally. The escape‑route shaping from earlier didn’t “carry” in the way I’d hoped, because the agents didn’t know the player’s position most of the time.

The honest diagnosis:

- Memory was missing. My policies were feed‑forward. In partial observability, that means amnesia every step.

- Credit assignment was still weak. Even with consensus and shaping, I was essentially training two independent action heads and hoping they’d synchronize.

This phase didn’t sink the project—it clarified it. The simple world was letting me get away with architectural shortcuts. The LOS world refused to.

What I learned:

- Partial observability without memory leads to short‑sighted thrashing.

- Reward hacks (reverse/stuck penalties) shape motion, not coordination.

A slower comparison of reward ideas (with feel, not just numbers)

I want to linger here because the rewards ended up defining the “feel” of each phase:

-

Independent DQNs — felt like two kids sprinting for the same ball. Lots of collisions. Some goals by accident. Not a team.

-

Shared team reward — felt like a group project where one person carries it. If someone else will finish and you get the same grade, why sweat?

-

Different per‑agent reward — felt like a time trial. Everyone became faster, but no one covered the weak side.

-

Consensus + simple reward — felt like we put a sticky note on the whiteboard: “try not to overlap.” It helped reduce identical mistakes but didn’t change incentives.

-

Escape‑route shaping + consensus — finally felt like intelligent pressure. When the player’s options shrank, capture didn’t need to be forced. It emerged.

-

LOS + penalties + exploration — felt like trying to play with one eye closed and no memory of the last second. Not fair, but also realistic. It pushed me to accept that architecture matters as much as reward design.

What I’ll do next (and why)

Two lessons survived all the experiments:

-

The escape‑route signal is gold. It encourages the agents to learn geometry, not just greed. I’m keeping it.

-

Collaboration needs structure. I can’t expect independent DQN heads to discover stable roles under LOS. I need either a centralized critic (e.g., COMA/MAPPO‑style) or a value mixer (e.g., QMIX‑style) to give a clear team objective during training. And I need memory—a small GRU/LSTM—to make the LOS world learnable at all.

Closing thoughts

This is part of an ongoing journey to understand how to build agents that can collaborate. I'm not sure if this is the right path, but it's a fun one to explore.

On top of that, I am happy that I am able to revive my love for reinforcement learning. I've been away from it for a while, and it's nice to be back.